Renaissance & Baroque Town Planning:

Florence’s Piazza Annunziata and Wren’s Plan for Post Fire London

By Anthony Morassutti

Awareness of town planning in the epochs of the Renaissance and, later, the Baroque period of architecture in Europe was emergent. Borne from the medieval castle-centric hodge-podge of unplanned towns, whose randomness seems more a product of complacence and self-preservation than of civic order and pride, town planning emerges as a doctrine that “aim[ed] at cohesive and unified composition.” (Moughtin 63) Florence’s Piazza Annunziata and Christopher Wren’s Plan for Post-Fire Londonare two examples of Renaissance and Baroque town planning, respectively, which will be examined to illustrate the developments present during these periods in the history of urban design.

Built during the 15th Century in the city-state of Florence, the Piazza Annunziata is a remarkable example of setting public and commercial buildings in an urban environment to create an open-air civic area. The resulting Piazza is a concept that is still reflected in modern Urban Planning, exemplified in Toronto by examples such as such as Toronto’s Nathan Philips Square and Dundas Square. The buildings that create the Piazza were erected at different times during Florence’s

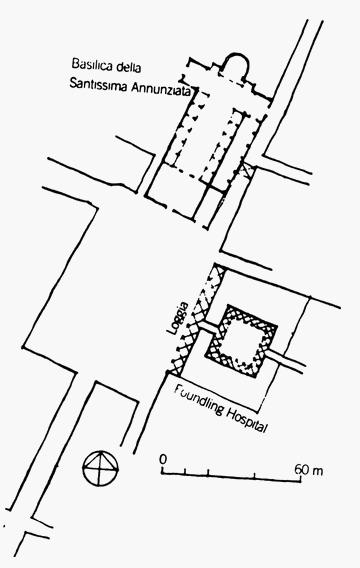

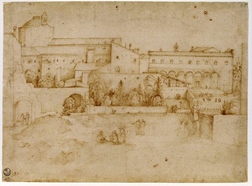

history, leading with the Piazza’s namesake the Basilica Santissima Annunziata (originally a 14th century Gothic church). It was redesigned and enlarged to Renaissance standards by Michelozzo de Bartolomeo and Leon Battista Alberti, and rebuilt beginning in c1444. (Heydenreich and Lotz 20) The earliest original building to be added to the developing piazza was the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents) in 1419, designed by Filipo Brunelleschi who received the commission from the Silk Guild to construct the Ospedale, a religious institution committed to the care of the city’s infants. (Ching, Jarzombek, and Prakash 446) It would not be until approximately 90 years later, that a mirror to the Innocenti would be built by architect Sangallo the Elder in the form of a nearly identical building, “completing the greater cumulative effect of a perfectly symmetrical piazza.” (Sloan 1)

Social welfare hospitals were a source of pride to the residents of the Tuscan city, who called upon their architects to considerably deviate from Florence’s normally subtle urban planning. (Mayernik 162) One example of such bold planning is seen in Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti in its design of a special door which would allow parents to anonymously put their babies up for adoption. (Ching, Jarzombek, and Prakash 446) The design of the Ospedale expresses architecture as a progressive social valve, where one could make private choices without fear of social consequence. Consider that: Monasteries were often the sole refuge of orphans; Brunelleschi therefore brought not only the physical form of the cloister but its associations to the res publica. This functionally and symbolically transformed the nature of public space into a more literal mirror of the civitas dei like that usually reserved for the monastery. (162 Mayernik, latter italics in original)

Furthermore, the beautiful cerulean blue tiles depict swaddling children that adorn the loggia of the Ospedale at regular intervals above each column. The covered loggia invites the public to gather within and not transverse it, as public covered space was precious. (Ching, Jarzombek, Prakash 446) In addition to the rhythmic 7-bay arcades of the loggias of the Basilica and 9-bay arcade of the Ospedale, the Piazza contains the Mannerist fountain by Pietro Tacca, and a tribute statue to

the square’s patron, the Arch Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand I de’Medici. (Hibbert 279) In my opinion, both the fountain and the statuary tribute act as signposts between the architecture highlighting the history of the city and the Medici patron. These pieces add warmth in an otherwise cold stone plain. Directly opposite to the Santissima della Annunziata is the Via dei Servi, the roadway that connects the Piazza Annunziata to the Duomo, running almost due southwest from between the Ospedale. (See Appendices 1 and 2) The architects of the buildings comprising the Piazza Annunziata have achieved aesthetic balance, while creating a contained private space for the public.

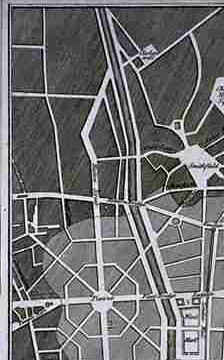

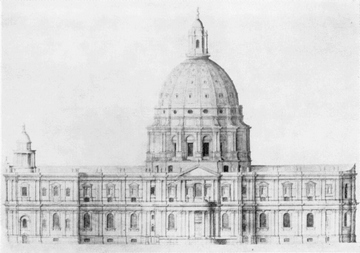

Following the Great Fire of 1666 in London, England, an immense challenge was presented to legislators and urban planners alike, to usher in a new design for their Empire’s capital. (See Appendix 3) The development of the British capital during the Baroque period was greatly influenced by its master architects, notably Sir Christopher Wren. His vision and stewardship coincided with an opportunity to redesign almost an entire city, as nearly eighty-eight percent of London had been destroyed in the fire. (Whinney 37) Wren, General Surveyor to King Charles II at the time, submitted his plan to rebuild London only five days after the flames had been brought under control. (Summerson 205) He, along with two others hand picked by the King, Roger Pratt and Hugh May, joined with the Corporation of the City of London’s choices, Peter Mills, Edward Jerman, and Robert Hooke, to comprise a joint Rebuilding Commission between the monarchy and municipality. (Jardine 254) Ultimately, under Wren’s plan, the Joint Commission constructed over 50 churches and cathedrals, replaced upwards of 12,000 houses for the displaced mass of approximately 65,000 people (Jardine 251), and laid wider roadways. Once

legislation for the rebuilding passed with the Act for Rebuilding the City of London, design and construction lasted for twenty years, with the exception of certain church steeples, interiors, and negligible details. (Summerson 205, 211) Some selected examples of the buildings that were constructed at this time are St. Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1710), The Royal Exchange (completed 1671), Customs House (1669-71), Brewer’s Hall (c1670), St. Mary-le-Bow (1670-6), and St. Lawrence Jewry (1671-7). (See Appendix 4)

The Act set out codes and details (e.g. floor heights, roof types, etc.) that were strictly adhered to by Wren and his posse, in effect legislating building procedure. (Summerson 205) It is remarkable to me that any government body is capable of moving so swiftly and decidedly on any issue, especially the redefinition of the capital city of the British Empire. It speaks volumes of the kind of trust invested by the King and British people in Wren and his stable of surveyors and designers. The gauntlet thrown down at Wren’s feet by the King and his brother the Duke was a mission to invoke a “Restoration in London”, to achieve, “a new, modern world capital suitable for [his] Kingdom”. (Jardine 255) Private business and wealthy individuals funded the urban reconstruction, as well as

proceeds from the new Coal Tax introduced in 1667 as a means to help pay for reconstruction. (Summerson 206) Wren’s Plan for post-fire London also set new standards for town planning in England. The Great Fire of London necessitated “a new structural standard of brick domestic architecture [that] was set up for the whole country.” (Summerson 210, italics in original) When faced with the choice of how to rebuild, Wren pleaded with the King to allow for new construction techniques and urban planning. He made his case in a memo called Consequences of Rebuilding the City upon the old Foundations, where Wren insists that London suffered great damage in the Fire “...manifestly proceeding from the Closeness of the Streets and the Combustible Materials” (Jardine 263, capital in original). In essence, making his case for more separation between building using wider roads, and the employment of non-combustible materials such as stone and brick. The Great Fire of London not only provided the British with an opportunity to build a new royal city, it also changed how town planning would be designed, implemented, and rigorously regulated.

The cities of Florence and London grew detached from medieval architectural notions. King’s castles or holy monasteries at a town’s centre now were accompanied by a public square, as in the case in Florence. London was redesigned to encourage growth, development, commerce, safety, and worship. The progressive designers of these cities, such as Brunelleschi, Michelozzo, and Wren, accelerated the evolution of modern town planning, the effects of which can still be felt in contemporary architecture.

APPENDICES:

Works Consulted

Anglican Campus “In the Beginning…:The Great Fire of London – 1666.” Jan. 21st, 2007. http://www.angliacampus.com/education/fire/london/history/greatfir.htm.

Ching, Francis D.K. and Jarzombek, Mark M. and Prakash, Vikramaditya. A Global History of Architecture. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2007.

City of London. “The Return of Temple Bar to the City of London.” Jan. 21st, 2007. http://www.thetemplebar.info/History/Sir_Christopher_Wren.htm.

Discover Firenze. “Piazza Santisima Annunciata.” Jan. 23rd, 2007. http://www.discoverfirenze. com /ssanunciate/index.html.

Exciting Postcards. “Wren’s City Churches: The Postcards of H.R. Allenson.” Image of St. Lawrence Jewry. Jan. 21, 2007. http://mysite.wanadoo-members.co.uk

/exciting2/allenson/index.html.

Explore St. Paul’s “The Great Fire of London.” Jan. 21st, 2007. (6th image down: Ruins of St. Paul’s, 12th image down: The Monument) http://www.explore- stpauls.net/oct03/

textMM/GreatFireN.htm.

Explore St. Paul’s Cathedral. “Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723).’ Jan. 25th, 2007. Image of Customs House. http://www.explore-stpauls.net/oct03/textMM/WrensTombN.htm

Friends of the City Churches. “St. Mary-Le-Bow.” Jan. 28th, 2007. http://www.london-city-churches.org.uk/Churches/St%20Mary-Le-Bow.htm

Genmaps: Old and Interesting Maps of England, Wales, and Scotland. “holler_London_1666.” Jan 22nd, 2007. http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/

~genmaps/genfiles/COU_files/ENG/LON/hollar_london_1666.jpg

“George Vasari: The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects” Jan. 27th, 2007. http://easyweb.easynet.co.uk/giorgio.vasari/micheloz/micheloz.htm.

Heydenreich, Ludwig H. and Lotz, Wolfgang. Architecture in Italy. London, England: Penguin Books, 1974.

Hibbert, Christopher. The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1979.

Jardine, Lisa. On a Grander Scale: The Outstanding Life and Tumultuous Times of Sir Christopher Wren. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2002.

L’Uomo del Rinascimento: Leon Battista Alberti, e le Arti a Firenze Tra Ragione e Bellezza. “The Exhibition’s Works: Veduta della piazza della Santissima Annunziata by Fra. Bartolomeo.” Jan. 23rd, 2007. http://www.albertiefirenze.it/english/mostra/opere/

sez4/sez4_92.htm.

Mathematik und Kunst. “Christopher Wren.” Jan. 21st, 2007. http://www.math-inf.uni-greifswald.de/mathematik+kunst/kuenstler_wren.html

Mayernik, David. Timeless Cities: An Architect’s Reflections on Renaissance Italy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Books Group, 2003.

Mio Si To Web. “Il vostro nido a Firenze.” Jan. 27th, 2007. http://www.miositoweb.com/firenze/firenze1.htm.

Moughtin, Cliff. Urban Design: Street and Square. Burlington, Massachusetts: Architectural Press, 2003.

Museums of Florence, The. “Florence Map.” Jan. 27th, 2007. http://www.museumsinflorence.com/landscapes/Florence_map.html.

Whinney, Margaret. Christopher Wren. London, England: Praeger Publishers, 1971.

Sloan, Kevin W. “Second Man Missing: Lawrence Halprin and Associates’ 1970s Heritage Plaza in Forth Worth remains uncompleted and undermaintained.” Landscape Architecture: The Magazine of the American Society of Landscape Architects. April Edition (2003): Jan. 28, 2007 http://www.asla.org/lamag/lam03/april/feature1.html

Students Ville: Florence Photo Gallery. “Tacca Fountain.” Jan. 23rd, 2007. http://www.florencephotos.com/pic.asp?iCat=50&iPic=287

Summerson, John. Architecture in Britain: 1530 to 1830. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd., 1953.

University of Pennsylvania. “Transatlantic Traffic: Philadelphia, London, and the World: Rebuilding London after the Fire.” Jan. 21st, 2007. http://www.english.upenn.edu/

Undergrad/Courses/Spring02/traffic/rebuildinglondon.html.

University of Pittsburg(?). “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture: England: London: Maps.” Jan. 26, 2007. http://vrcoll.fa.pitt.edu/medart/image/England/

london/Maps-of-London/London-Maps.html.

Untrique Paratus. “Florence Trip: 4 April 2004.” Jan. 23rd, 2007. http://www.s-phase.com/blog01/archive01/2004_04.html.

Vivere Firenze “Galleria Photografica: Verso Piazza della Santissima Annunziata.” Jan. 23rd, 2007. http://www.comune.firenze.it/viverefirenze/itinerario3/schedef/3/

scheda3.html.

Weale, John. The Pictorial Handbook of London (London: Harry Hohn, 1854) “St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.” Jan. 21st, 2007. http://www.english.upenn.edu/

Projects/knarf/Gifs/stpauls2.html.